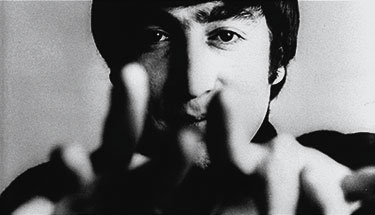

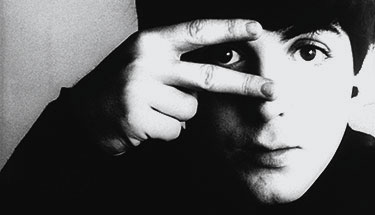

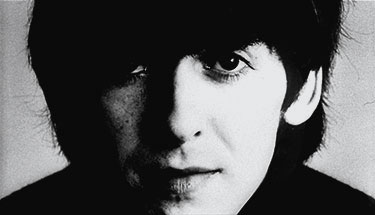

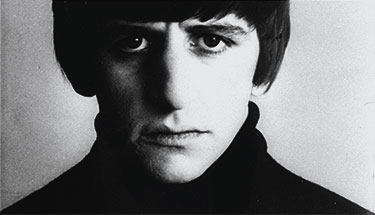

Meet the Beatles! Just one month after they exploded onto the U.S. scene with their Ed Sullivan appearance, John, Paul, George, and Ringo began working on a project that would bring their revolutionary talent to the big screen. A Hard Day’s Night, in which the bandmates play wily, exuberant versions of themselves, captured the astonishing moment when they officially became the singular, irreverent idols of their generation and changed music forever. Directed with raucous, anything-goes verve by Richard Lester and featuring a slew of iconic pop anthems, including the title track, “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “I Should Have Known Better,” and “If I Fell,” A Hard Day’s Night, which reconceived the movie musical and exerted an incalculable influence on the music video, is one of the most deliriously entertaining movies of all time.

dir. Richard Lester • UK 1964 • Black and White • 1.75:1 • 87 minutes

About the restoration

Using the latest in digital restoration technology, the Criterion Collection was able to restore A Hard Day’s Night from the 35mm original camera negative, which, though incomplete, was in excellent condition. The missing material was taken from two original interpositives. The image was scanned in 4K resolution on a Scanity film scanner to retain the character of the film’s original printing stock without any generational loss, and the raw data was carefully treated using a variety of digital tools to remove dirt, scratches, flicker, and other damage. The final result was approved by director Richard Lester, and is in its original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.75:1.

A Brief History

In early 1964, the Beatles were at their peak. They’d been working together for six years, had been a recording act on a major label for eighteen months, and were the first “rock band”—a collective with equal, individual personalities. In the UK, their first single, “Love Me Do,” had hit the Top 20; their second, “Please Please Me,” had reached no. 1; and by the end of 1963, they had had three more no. 1 singles and two no. 1 albums. And after scattered releases in the U.S., they cracked the American market with “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Released at the end of 1963, the single went to no. 1 on the American charts, fueled by media reports of mobs of screaming British fans following the band everywhere they went.

The same hysteria greeted the band upon their arrival in New York City on February 7, 1964, and was only enhanced by their charming, witty press conferences. Newspapers and television were full of reports of “Beatlemania” and “the British Invasion”—and, of course, 73 million people tuned in to watch the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show on February 9, smashing the previous record for the largest TV audience.

In the meantime, back in the UK, “the Beatles movie” was in development. United Artists brought on board producer Walter Shenson to make a film with the band. Shenson had previously hired Richard Lester to direct the film The Mouse on the Moon in 1963, and when he mentioned his new project to Lester, the director “jumped on the chair in the Hilton Coffee Shop and said, ‘My God, can I direct it?’ ”

Shenson agreed, as did the band. According to Lester: “The Beatles had seen me in interviews; and I was musical, and they liked that . . . But the final [reason] was my having accepted that the style, the format [of the film, needed to] create a surrounding similar to the way they actually lived.” To ensure the film maintained a realistic grounding, Alun Owen, whose depiction of Liverpool in the television play No Trams to Lime Street had impressed the band, was chosen as scriptwriter.

When the Beatles returned to England in late February, they quickly went about recording the first batch of songs for the film. Settling in at EMI Studios in Abbey Road, London, they cut “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “And I Love Her,” “I Should Have Known Better,” “Tell Me Why,” “If I Fell,” and “I’m Happy Just to Dance with You” in only three days. They needed to work quickly, as principal photography was set to begin the following Monday.

Filming began on a train, and it was soon obvious that Lester was the perfect director for the project. Easily guiding the band through their performances, Lester relied on improvisation rather than rehearsal, creating a freshness that was clear on-screen. “Before we started, we knew that it would be unlikely that they could (a) learn, (b) remember, or (c) deliver with any accuracy a long speech. So the structure of the script had to be a series of one-liners,” Lester later noted. “This enabled me, in many of the scenes, to turn a camera on them and say a line to them, and they would say it back to me.”

Just as fresh was Lester’s visual style. Shooting with multiple cameras to capture every angle and letting the energy of the band drive the film, the director mixed techniques from narrative films, documentary, the French New Wave, and live television to create something that felt, and was, spontaneous. “I have seen directors who write down a list of scenes for the day and then sit back in a chair while everything is filmed according to plan,” Lester has said. “I can’t do that. I know that good films can be made this way, but it’s not for me. I have to react on the spot. There was very little structure that was planned, except that we knew that we had to punctuate the film with a certain number of songs.”

And when filming was nearly over, there was still one song to write and record—the title track. Except that the film had yet to be titled. “During a lunch-break conversation, John Lennon mentioned to me that Ringo misused the English language,” said Shenson. “When I asked for an example, he said, ‘Ringo called an all-night recording session “a hard day’s night.” ’ John laughed, but I said, ‘My God, that would make a marvelous title.’ ” Title in hand, John and Paul went back to the studio and wrote one of their most memorable songs to order.

Shot, edited, and mixed in only four months, the film premiered on July 6, 1964, at the London Pavilion theater, with Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon in attendance. Four days later, the film had its Liverpool premiere, where the band greeted over 200,000 hometown fans.

The Beatles were now the most famous band in history. A musical and cultural revolution had begun, and it was through A Hard Day’s Night that audiences all over the world came to feel that they knew John, Paul, George, and Ringo personally.

The band’s unprecedented success made the film an international sensation, but fifty years later, other reasons for its lasting impact are clear. Its synthesis of antiauthoritarianism, humor, and sheer cinematic exuberance helped lay the groundwork for the New American Cinema of the seventies, and its song sequences paved the way for what would become the music video. Thanks to the energy and charisma of the Beatles and Lester’s inexhaustible creativity, A Hard Day’s Night remains a milestone of contemporary culture.