The Story of a Poem

In 1972, musician Leon Russell was looking for a filmmaker to make a documentary about him, so he and his record producer, Denny Cordell, called the American Film Institute in Los Angeles to ask who might be a good fit. AFI suggested an exciting filmmaker named Les Blank, who had demonstrated his unique skill at documenting musicians with The Blues Accordin’ to Lightnin’ Hopkins (1968) and A Well Spent Life (1971).

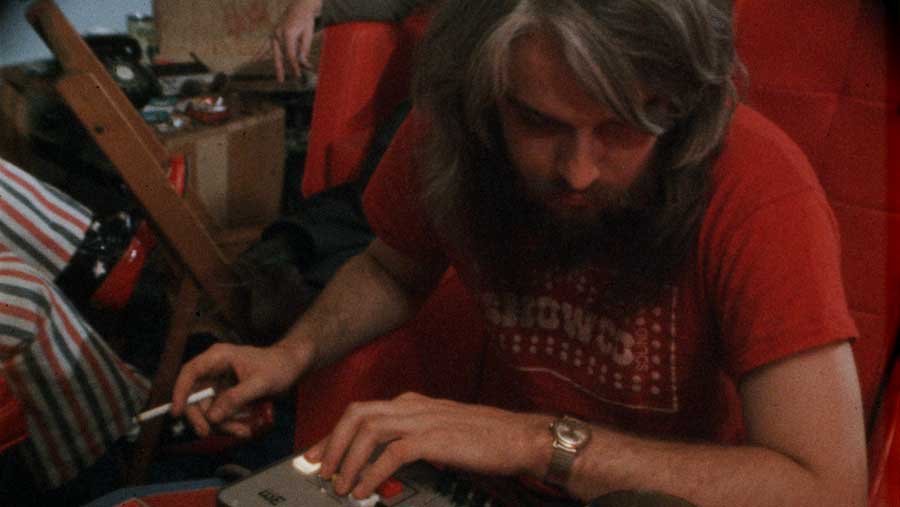

In May of that year, Blank and his collaborator Maureen Gosling, fresh from shooting hours of footage in Southwest Louisiana about black Creole music and culture, were making a pit stop in Dallas for the USA Film Festival. It was there that Blank was informed that Russell and Cordell were trying to get in touch with him. Though he had not heard of Russell, Blank was intrigued, so he and Gosling immediately headed north to Oklahoma and met the two men at Russell’s recording complex, Paradise Studios, in Grand Lake o’ the Cherokees, about ninety miles northeast of Tulsa. Blank agreed to shoot a film about Russell as long as he could set up shop at the studio and simultaneously edit his Louisiana footage (which would ultimately become two separate 1973 films, Dry Wood and Hot Pepper).

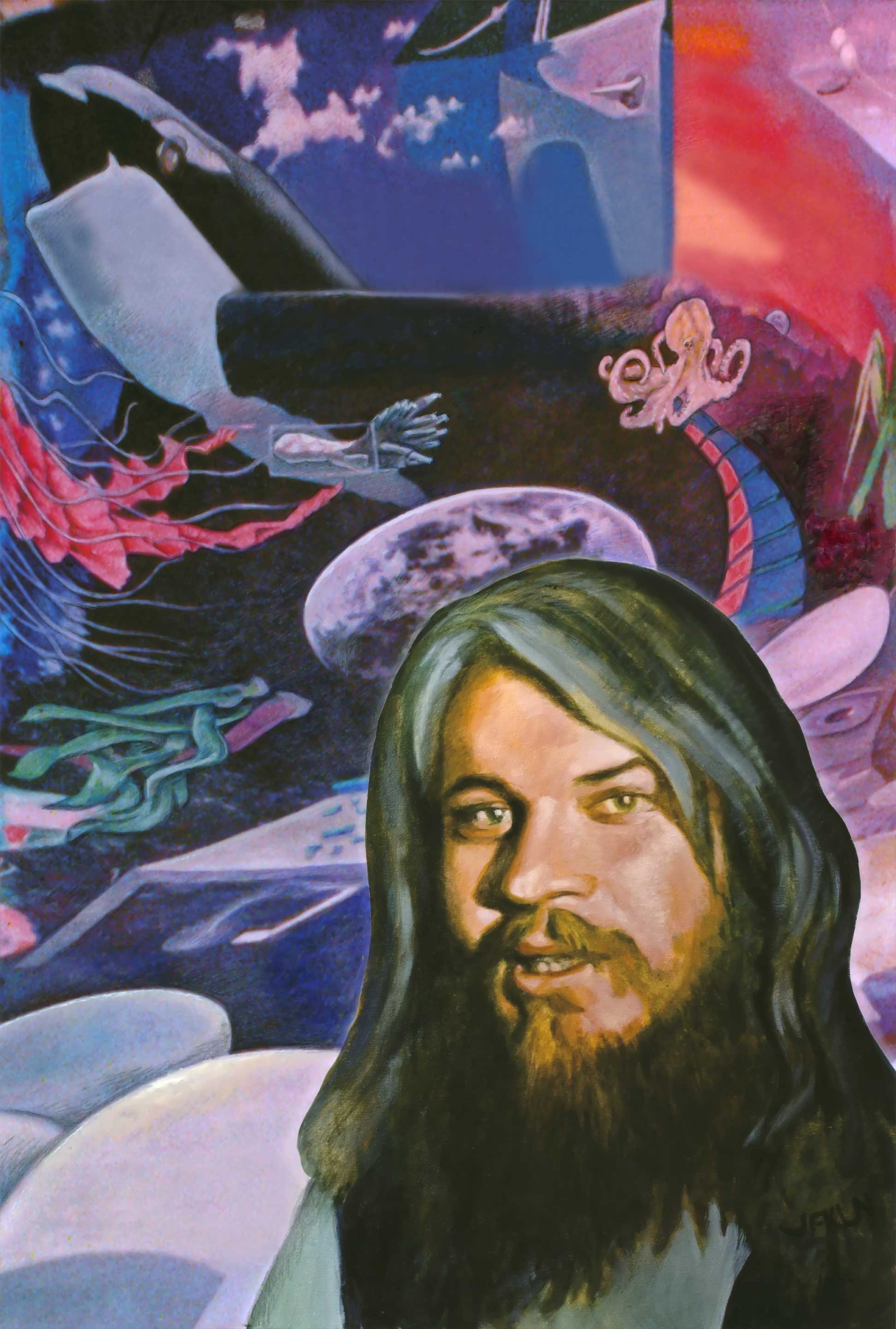

Blank and Gosling set up his Moviola editing machine and started working day and night. Their new quarters, according to Gosling, consisted of “a five-room floating motel on Leon’s property, which had been used by fishermen in the property’s last incarnation as a fishing dock retreat.” The recording compound was frequented by other artists and musicians, and the environment was communelike. It soon became clear to Blank that the film would be about not just Leon Russell but an entire community of people, including painter Jim Franklin, whom Russell had brought in from Austin, Texas, to paint the walls of his recording studio, but who discovered a more interesting canvas in the blank walls of an empty swimming pool. Blank also filmed other musicians who came through, including Eric Andersen, Charlie McCoy, and Willis Alan Ramsey.

Blank kept his camera rolling over the course of two years, ending up with nearly sixty hours of 16 mm footage. This included Russell playing music—in rehearsals, recording sessions, and concerts in New Orleans and Anaheim, California—as well as performances by such music legends as Willie Nelson and George Jones. Yet Blank was ultimately after something more ineffable and atmospheric, something that reflected the odd juxtaposition of the state-of-the-art music studio and its rural surroundings. The result, A Poem Is a Naked Person, is more a collagelike, abstract film about a time and place than a straightforward portrait of a performer. Thus, footage of a building demolition is as crucial to the overall tapestry as Russell’s performances of his singles “Tightrope” and “A Song for You.”

The first cut, which clocked in at just over 100 minutes, was accepted into the 1974 Cannes Film Festival, but the screening was canceled when the print didn’t arrive in time. As history would have it, the film wasn’t released for another forty years. Blank was still a comparatively little-known filmmaker at the time, and while this movie reflects what we now recognize as the genius of one of America’s premiere chroniclers of music and culture, it was not what Russell and his team were expecting, and Russell did not approve the release. Blank had only a work-for-hire contract and therefore didn’t have the rights to the finished product, although he was permitted to show the film at nonprofit venues if he was there in person.

Blank continued to work on the film, shaving off nearly eleven minutes over the years. He considered this essentially lost film his masterpiece, and he always wished it could see the light of day. In early 2013, two months before Blank died, his son, filmmaker Harrod Blank, made contact with Russell via Facebook—the first time the Blank family had been in touch with the musician in nearly forty years. The two continued to communicate, and met face-to-face when Harrod attended Russell’s concert in Oakland, California, in October. That month, encouraged by their friendly encounter, Harrod began work restoring and remastering the film in New York, even though Russell hadn’t yet formally given his blessing to an official release. Working from various elements, Harrod and his collaborators tried their best to match Blank’s most recent cut, a ninety-minute version from 2011.

In 2014, after Russell had seen a remastered Blu-ray of the final version of A Poem Is a Naked Person, he made an agreement with Harrod Blank to release the film. Harrod decided to work with Janus Films on the theatrical release, as he was pleased with the deluxe treatment Janus’s sister company, the Criterion Collection, had just given his father’s work with the box set Les Blank: Always for Pleasure. A Poem Is a Naked Person finally had its official Janus Films premiere at the South by Southwest festival in Austin in March 2015, attended by Russell, who received a standing ovation after the screening. We can safely assume that Les Blank would have been thrilled to be there. Says Harrod, “It was his dream to see this released. I sort of put my life on hold to see this through.” When Russell was asked why it took so long for the film to come out, he responded, “I don’t know. Maybe because it needed to come out now.” With the benefit of hindsight, everyone, not least Russell, recognizes this film as one of Blank’s greatest achievements.